I am the co-editor of a future book on intelligence in a colonial context. If you are interested in contributing, read our call for papers below and send me an abstract to vincent.hiribarren@kcl.ac.uk.

Call for papers: Intelligence in a Colonial Context

Edited by Jean-Pierre Bat, Nicolas Courtin and Vincent Hiribarren

Second GEMPA (Groupe d’études sur les mondes policiers en Afrique) edited collection

The second GEMPA edited collection is a continuation of the work undertaken by the GERN (Groupe Européen de Recherches sur les Normativités – Georgina Sinclair and Chris Williams, The Open University/ICCCR, Margo De Koster, Xavier Rousseaux, Catholic University of Leuven/CHDJ and Emmanuel Blanchard, CESDIP/Paris). It traces its origins back to colonial Policing Studies led by the Colonial and Postcolonial Policing Group (COPP) at the Open University (UK) and develops the inquiries of our first edited collection, Maintenir l’ordre colonial, Afrique et Madagascar, XIXe et XXe siècles (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012).

In the Anglophone academic world, Intelligence Studies have paved the way for a reappraisal of Western state policies by analysing intelligence as an attribute and a manifestation of the State. Our aim is to extend this approach to the colonial and imperial world.

This collective study does not claim to be exhaustive and will cover the end of the nineteenth century to the twentieth century and will garner studies on territories located on different continents and governed by a multiplicity of colonial powers. It will interrogate the practical dimensions of intelligence in the colonial empires by assessing similarities and differences between metropole and colony. Our case studies will consequently tackle the evolution of both intelligence practices and theories.

Intelligence Studies has often overemphasised the role of intelligence undertaken by and in the name of the State. This book seeks to go beyond the institutional approach often adopted by Intelligence Studies. Whist an important source, intelligence reports cannot be the sole basis upon which History is conceived as they are written from the point of view of the State not the colonised. Nonetheless, without totally discarding this approach, Intelligence in a Colonial Context would like to consider the circulation of information in its totality.

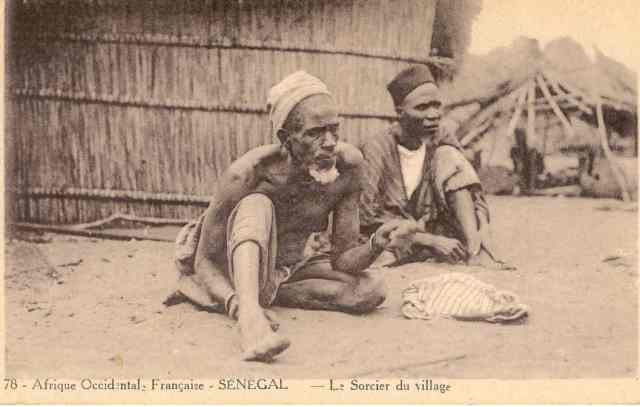

Despite their strategic role, the intelligence colonial institutions are only one of the many relays and catalysers of information in a colonial context and this is something we seek to emphasise. We do not consider intelligence as an omniscient instrument stemming from an all-powerful colonial toolkit. On the contrary, we argue that colonial empires, whether in the metropole or the colony, were particularly blind and did not perceive societies as they were, but as they fantasised them. In consequence, Intelligence in a Colonial Context will reassess the primary sources traditionally used by Intelligence Studies scholars.

The Foucauldian metaphor of sight could be extended to State intelligence agencies which were particularly myopic in that they did not go beyond a blurred and superficial understanding of the colonised societies. They could also suffer from a form of strabismus as they distorted reality. Finally, intelligence could be simultaneously longsighted as they often exaggerated resistance and contestation movements directed against the colonial State, sometimes triggering paranoid security responses. Such distorted vision consequently altered what constituted the main objective of the political power, i.e. the informing of the colonial State.

Michel Foucault has already analysed the correlation between the lack of power of the State and the increasing role of surveillance in Western societies and we seek to develop this. In a similar vein, Crawford Young has stressed the same phenomenon in colonial Congo. For Young, it was because of its weakness that the Congolese colonial State was so violent. This last study has led to a discussion on the representativeness of Belgian Congo, but proves that a similar debate is necessary in an intelligence context since so many scholars dealing with Intelligence Studies treat colonial societies as passive objects.

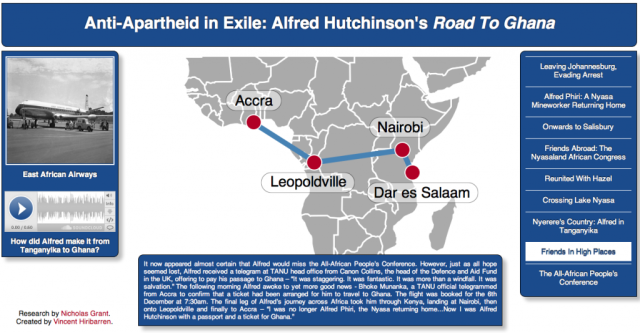

The GEMPA considers that the creation, evolution and development of intelligence agencies remain a pivotal point for the circulation and diffusion of information. However, we would like to focus on a broader understanding of the questions of intelligence and information. Indeed, the real informers and real information are to be found elsewhere. Since the beginning of European imperial expansion and the creation of colonial empires, intelligence and the circulation of information are everywhere and consubstantial to colonial societies.

We would like to go beyond a minimalist approach which only considers intelligence through the professional institutions under construction in the modern period. Our objective is to broaden the subject’s perspective by analysing intelligence practices in colonial context at different levels (from the village to the city to the colony or metropole as a whole) and for different social backgrounds. Whether public or private, information is neither monopolised by the coloniser nor intelligence professionals but is often publicly used for a multiplicity of purposes. This explains why we would like to focus on non-state actors producing or carrying information as they are not part of the army, the police or the colonial administration.

Intelligence in a Colonial Context aims at showing that information and intelligence are as much the backbone of the State as that of colonial societies.

We invite the submission of papers on the following themes:

1) The Colonial State as seen through its intelligence agencies

2) Intelligence “from below” (unpublished histories of informers; intelligence agents or state; parastatal and non-state intelligence networks)

3) Subaltern Intelligence Studies (the other side of the coin, i.e. the study of information and communication networks; the analysis of “informal” informers who worked for the colonisers; parallel or semi-parallel networks)

Submitted papers will analyse “intelligence in action” focusing on the creation and evolution of State, parastatal or non-State intelligence practices. Ideally, authors will give a similar place to both intelligence actors and users and will write a cultural and social history of men and women whose professions or activities deal with information and intelligence in a colonial context.

Provisional Timetable

Deadline 1: 30 March 2014. Send one page to the book editors (main argument, primary sources, and plan). Answer from the editors before 15 April 2014.

Deadline 2: 1 June 2014. The selected authors will send the first draft of their chapter to the book editors.

In their final published version (including footnotes and bibliography), the essays should be around 5000-6000 word long.

Contact

Jean-Pierre Bat (bat.jeanpierre@gmail.com), Nicolas Courtin (ncnicolascourtin@gmail.com), Vincent Hiribarren (vincent.hiribarren@kcl.ac.uk).