According to a 1974 UN FAO report 300,000 people, predominantly the northern rural poor, died during the 1973-1974 Ethiopian famine. There are a plethora of factors that created this famine from the imperial feudal system to the cumbersome reaction by the international community. However, in recent academia the focus has shifted to the merits and applicability of Sen’s entitlement theory and the food availability decline (FAD) model to the famine of northern Ethiopia. Amaryta Sen’s theory of entitlement, first proposed in his iconic book Poverty and Famines (1981), states that famines occurs when an individual’s entitlement collapses into the ‘starvation set’ caused by either a contraction in endowments (crops fail or livestock die) and/or an unfavourable exchange shift (food prices rise, wage or asset prices fall), which results in a decreased terms of trade with the market for food and the birth of famine. Contrary to Sen many academics argue that FAD was the cause of starvation, a basic lack of internal infrastructure meaning that no food entered the northern provinces from the surplus areas during the famine period. Essentially, did peasants not have enough money to buy food or was there not any food to buy?

The Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture Report of 1972 stated that output for 1972-1973 was 7% lower than the previous year, a fall in production that was not significant enough to cause the severity of the 1973-1974 famine. This has led many to question the validity of the FAD theory, especially Amaryta Sen who argues that there was a collapse in purchasing power (as most of the peasants’ income would normally come from the crops that failed) and thus the market did not direct food to the Wollo region.

However, those who advocate the FAD approach argue that even if there was sufficient demand in the region the transport network in Ethiopia was so poor that merchants did not perceive it to be profitable enough. Penrose estimates that in 1974 there was a total of 14k miles of road, with only 1/3 of that all weather, across the whole of Ethiopia and that 90% of people were more than a day’s walk from a road.

Sen offers two rebuttals of such an argument. First, there were two main functional highways in Wollo and they were both used to move food out of Wollo. Second, when there is a poor transport network there is a decline in supply and a subsequent rise in prices in that area yet there was no such spike in the Wollo region.

However, Kumar argues that Sen’s rebuttal is unfounded on two grounds. First, he states that Sen has severely underestimated the problems of transport, especially in the interior regions (he does not appreciate Penrose’s findings). Second, two articles by Cutler, Seaman and Holt suggest there was in fact a rise of food prices in the Wollo region during the famine, leaving Sen’s second point redundant. Furthermore, reports issued by the Ministry of Agriculture do not show the level of interregional trade that could balance out prices.

In conclusion, there was a decline in purchasing power of peasants in the Wollo region during the Ethiopian famine of 1973-1974, as Sen asserts, yet a poor transport network, combined with a 7% decline in production, caused the decline in food availability that led to famine.

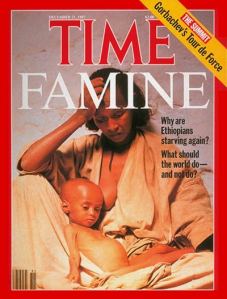

However, the Derg regime that took power in 1974 failed to understand and address these basic problems, subjecting Ethiopia to the horrors of famine once again in 1984, which prompted TIME to ask ‘why are Ethiopians starving again?’ (December 1987). If the government had addressed the basic structural constraints that caused the 1973-1974 famine, rather than focusing upon the creation of a socialist agricultural system, hundreds of thousands of lives may have been saved and Ethiopia’s blushes spared.

Nb. Sen’s entitlement theory cannot be rendered redundant because it is not applicable to the 1973-1974 famine in Ethiopia just as the FAD thesis is not flawless because it is valid in this situation; each famine has its own peculiarities and thus needs to be treated with its own individuality, detached somewhat from famines that preceded or followed it.

Brendan Lawson